Lana Ishkontana was killed by a story. The five year old Palestinian girl was excited to show her family her new holiday dress given to celebrate the the end of Ramadan when an Israeli bomb fell through the ceiling of their Gaza home, killing her, her three siblings and her mother. Lana's uncle Raed had stepped out to buy candy for the children and narrowly avoided the carnage, stating later “I wish I never left."

Lana Ishkontana was killed by a story. The five year old Palestinian girl was excited to show her family her new holiday dress given to celebrate the the end of Ramadan when an Israeli bomb fell through the ceiling of their Gaza home, killing her, her three siblings and her mother. Lana's uncle Raed had stepped out to buy candy for the children and narrowly avoided the carnage, stating later “I wish I never left."

Why is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict so depressingly enduring? Fully fourteen separate peace talks since 1978 have all ended in reliable failure. From the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BCE to the Crusades, scores of bloody battles have been waged over the centuries to control an arid and infertile patch of land smaller than New Jersey. While Israel may be lacking in natural resources, it is replete with competing religious narratives that have helped fuel over a dozen wars since 1947.

A central tenant of the Jewish faith is that Israel is the promised land gifted to them as the chosen people by the one true god through a covenant of religious obedience. Muslims hold that the Mohammad ascended to heaven from the Temple Mount in East Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam. Christians, particularly American evangelicals, believe that Christ will soon return from heaven to do battle with the antichrist in the Holy Land, necessitating the preservation of Israel through $4 billion in US military aid every year. Stories matter and many otherwise kind-hearted Jews, Christians and Muslims hold these narratives to be the divine truth apparently worth killing or dying for. If these narratives are literally killing children, where then did they come from?

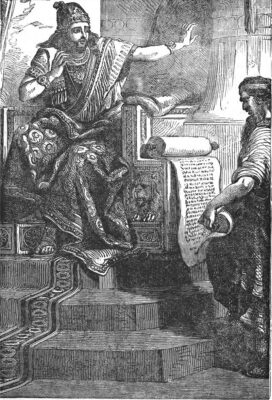

Anyone who doubts the power of myth-making should look no further than the enduring legacy of Josiah, an obscure Jewish patriarch who reigned as the largely forgotten sixteenth king of Judah, yet whose shadow still looms over intractable global conflicts twenty six centuries after his death. Josiah ruled during a pivotal time in Jewish history after the neighboring much larger nation of ancient Israel fell in conquest to the Assyrians causing refugees to pour into the comparatively smaller "kingdom" of scattered and unfortified villages.

Seeking to cement the influence of the Judah tribe over their longtime rivals now in disarray, Josiah instituted the Deuteronomic reform - a standardization of religious practices that included destroying local temples of sacrifice and prohibiting polytheism and idol worship that may have been widespread in now-vanquished nation to the north. Part of this campaign included writing the Book of Deuteronomy, an austere narrative and the last book of the Old Testament detailing God's wrath if the Jews defied his prescriptive will.

Seeking to cement the influence of the Judah tribe over their longtime rivals now in disarray, Josiah instituted the Deuteronomic reform - a standardization of religious practices that included destroying local temples of sacrifice and prohibiting polytheism and idol worship that may have been widespread in now-vanquished nation to the north. Part of this campaign included writing the Book of Deuteronomy, an austere narrative and the last book of the Old Testament detailing God's wrath if the Jews defied his prescriptive will.

Many scholars now believe that Deuteronomy was in fact the first book of the bible written, perhaps as a political effort to to unite the disparate Hebrew tribes under a single set of beliefs, customs and fictionalized history. Historians have puzzled that after centuries of searching, there remains no archeological evidence whatsoever of a united Jewish kingdom detailed in the biblical record preceding Deuteronomy. No King David. No Solomon's temple. No Egyptian record of the the Exodus.

A more likely explanation is that a common historical narrative was conjured up to meet the short-term political challenges of a small divided fiefdom sandwiched between the Iron Age superpowers of Egypt and Assyria. Central to this story the covenant between God and the Jewish people - the promise that land and security will provided in exchange for religious obedience. It is also important to note that Assyria was in rapid decline during the later reign of Josiah, creating a short-lived window to embrace local independence beyond the centuries-long indignity of being an Assyrian vassal state before Jerusalem fell to Babylon a few decades later.

Could much of biblical history have been invented merely to keep Josiah on the throne at a time when Jewish kings were routinely murdered by their retinue? While Josiah is long gone and largely forgotten, the enduring message of a chosen people and a promised land echoes through the ages within the intractable conflict in the Middle East, binding the hands of even the superpowers of today.

Josiah teaches us that narrative matters, perhaps more than even truth. Unless we can embrace a more universal narrative, more bombs will surely fall on the homes of more children like Lana.