We have been interrogating the natural world about the etiquette of existence. Observers seem particularly important to the unfolding of celestial events. Are there any empirical clues found in the evolutionary record on how sentient observers ought to treat each other?

A clue might lie in the delicate act of lobster sex. In order for a female lobster to reproduce, she must enter the rocky lair of a large dominant male who normally would be very happy to eat her. The "hen" must then shed her shell in order to expose her lobster lady parts, making her even more defenseless. After mating she is entirely dependent for days on her temporary sexual partner to protect her until her new shell hardens before parting ways. How does she begin this perilous conservation of love? With her pee. Specifically by squirting into the male's den an invertebrate version of a chemical called oxytocin that is ubiquitous within complex biology.

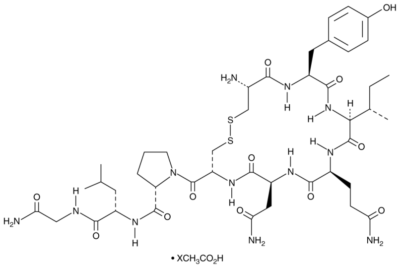

Nicknamed the Moral Molecule in a 2012 book by Paul Zak, oxytocin and its specific receptors in the brain seem to be the biochemical seat of sympathy, love, and trust - not just in humans but in almost all animals. Evolution does not typically accommodate extraneous luxuries, so what is so vital about such seemingly altruistic values? In the case of lobsters, being able to let down your guard within the normally cannibalistic culture of crustaceans is crucial for reproduction, and therefore the survival of the species. Survival of course is not just about reproduction, but also coexistence and oxytocin helps here too. The vast majority of the 7.7 billion people occupying the planet jostle through their crowded existence while actively avoiding conflict - a remarkable act of cooperation that is repeated on a daily basis.

There are obviously many social struggles around the world borne from injustice that need to be confronted. But in those those places in the world fortunate to have a baseline of prosperity and peace, our core desire seems to be to get along with neighbors and strangers alike. Is this merely the smug perspective of privilege? Perhaps. And if so, let's then consider another example beyond the minutia of human experience.

When Police raided an Atlanta crack house in 2001 they discovered three exotic animal cubs in appalling conditions that were kept as the curio trophies of a local drug dealer. An American black bear, a Bengal tiger and an African lion cub were taken to a local wildlife sanctuary to treat their various aliments, which has been their home ever since. Babaloo the bear had been tied up in the basement so long the harness had grown into his paw. While being operated on, Leo the lion and Shere Khan the tiger were noticeably stressed at being separated from their bear companion. To calm them down the sanctuary director decided to move them together in the same enclosure - an unusual arrangement that peaceably persisted for the next fifteen years.

Babaloo grew to 1,000 lbs and the lion and tiger both weighed in at about 350. All were male animals that would never encounter each other in the wild, although Siberian tigers have been know to attack full-grown brown bears. Instead these apex predators from three different continents lived together for over a decade. To the delight of the sanctuary visitors, BLT (bear, lion tiger) seemed to enjoy snuggling, wrestling and typically slept together a large furry heap. Leo died in 2015 and Shere Khan passed three years later, leaving a behind their bereaved bear companion.

With abundant resources and no reason for conflict, three massive alien animals - only one of which evolved to live in a social group - were happy to enjoy each others company and visibly unhappy if ever separated. Like the lobster, their oxytocin receptors were likely designed to mediate reproduction within their own species. However in the special circumstance of the sanctuary, these same brain receptors seemed to work just fine on each other. The last common ancestor of a lion and tiger was about six million years ago. Bears and cats last shared a common species 42 million years ago. Humans and dogs have enjoyed each others company for millennia.

Science has no answer to the puzzling question of interspecies friendship, but individual scientists are no doubt among the millions of people who enjoy sharing internet memes on the subject. Why? Because we all enjoy a good flush of oxytocin, the molecule that for some reason seems baked into sentient biological existence.

Would an artificial intelligence enjoy sharing videos of LOL humans? An AI would of course be immune to oxytocin, but hopefully not the kindred glow of shared experience. Here's hoping that they find us cute...