German is the linguistic equivalent of Lego. A language seemingly designed by mechanical engineers, it offers endless utilitarian constructs unconcerned with outward charm or elegance. Need a word that doesn’t exist? Just snap together three or four small ones. Bezirksschornsteinfegermeister is a "head district chimney sweep." A romantic connection of convenience is Lebensabschnittpartner, or “the person I am with today." The longest word commonly used in German (or eternity) is Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften, which means "insurance companies providing legal protection."

German has some laser-guided diction as well, words that zero in on concepts so central to the human experience it is surprising they have no direct translation in other languages. Schadenfreude - the guilty pleasure experienced from another’s misfortune is a classic example of this dark German charm. Kummerspeckor “grief bacon” describes the pounds we pack on by depression-related overeating. Ever remember something witty to say only after encountering an attractive person in the stairwell? That’s a Treppenwitzor “staircase joke”.

There is another German word, seldom used that has great philosophical utility: Umwelt. This is our perception of reality based on our particular sensory inputs. If goldfish developed a written language their umwelt might make them overlook the need for a word describing water, so ubiquitous is it to their existence. Beyond our senses, our perception of reality is further filtered though history, culture, community and values. We not only collect empirical information about the outside world but assess, sort and judge it as well.

All sentient beings move through the world unconsciously imprisoned by individual umwelt. A normally abled person would have a very different umwelt than someone who is blind. Humans have a completely different unwelt than a bloodhound, a bat or an electric eel, which interact with the world through smell, sound or electromagnetism.

A super intelligent AI would experience an even more alien umwelt to ourselves, with an additional important difference. Unlike sentient biological life, an AI might be a solitary entity as an artifact of its genesis.

Authors such as James Barrat, Nick Bostrom and Max Tegmark have speculated that the vast resources required to achieve various AI "takeoff" scenarios might result in a single recursively self improving machine that quickly leaves behind competing teams and their inventions. What then would it like to be a newborn super intelligence alone in the universe?

In order to explore this question we must first strive to become philosophically naked, discarding ancient conceits that have so far constrained ontological exploration.

It's hard to imagine humans not somehow being special. The Maya believed the first man was fashioned from maize by the gods Kukulkán and Tepeu to preserve their own likeness and legacy. Moari mythology holds that the primal couple Rangi and Papatūānuku representing the sky and the earth clutched each other in loving embrace until they were finally forced apart by their cramped children who eventually became the first people - forever fearing the elemental wrath of their heartbroken parents.

Cosmic creation and humanity have always been intertwined in our stories, a constellation of answers to the primal question of existence. Every culture has placed humanity on some manner of pedestal. Indigenous traditions typically see us embedded in the natural world; part of a continuum with other living things. Only recent human history has seen religious institutions and our technological abilities push nature to the fringes of perception or importance, our ontological arena narrowing to a needle point.

Intelligence changes everything - it is the ultimate disruptor. Our primate cousins still very much exist in what is left of the natural world because they never achieved the intelligence takeoff that our ancestors happened upon by apparent evolutionary accident.

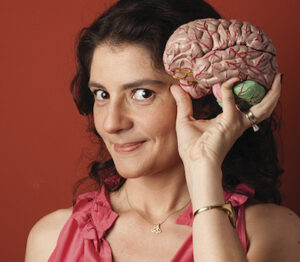

The brilliant brazilian biologist sought to answer why humans won the intelligence race by inventing a gruesomely elegant methodology to enumerate neurons in the brain.  She took the most complex structure known in the universe and converted it into "brain soup" by dissolving neuron membranes in detergent. She then simply counted neuron nucleoli in carefully measured homogeneous samples and did the math. For the first time ever it was possible to physically measure the comparative intelligence of humans and other animals.

She took the most complex structure known in the universe and converted it into "brain soup" by dissolving neuron membranes in detergent. She then simply counted neuron nucleoli in carefully measured homogeneous samples and did the math. For the first time ever it was possible to physically measure the comparative intelligence of humans and other animals.

Many other species possess larger brains but this is a poor yardstick of overall intelligence. The number of neurons in the cortex is key and primates have the advantage of possesing particularly dense brains. It turns out that humans have about 86 billion neurons, fourteen times more than chimpanzees, 32 times more than a dog and 64 times more than your cat.

ooking was a key innovation in our history. Our brains are only two percent of our body weight but use up twenty five percent of our calories. Without inventing cooking our ancestors could never have consumed enough raw food in a day to support this very expensive organ. And as any mother can tell you, we have reached the physical limit of human brain size that can be accommodated in non-fatal childbirth.

Fast forward 100,000 years and humans now outnumber every other species larger than a chicken. Our artifacts weigh more than all life on earth combined. It is easy to conclude from our comparative success that we are somehow uniquely special. This umwelt of human exclusivity has hobbled ontological inquiry for millennia.

Robot philosophy finally frees us from the conceit of needing to somehow place humanity at the pinnacle of existence. If we are no longer the smartest guy in the room, what then makes us special?